Editor’s note: This post isn’t about clinical narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), but about the way “narcissism” is sometimes misused in everyday discussions. Not all traits that get labeled as narcissism are harmful or rooted in pathology. We all need a sense of self-worth to function and thrive; narcissism as a personality trait is on a spectrum. And many of these traits can be deeply tied to survival and resistance in oppressive systems.

This conversation does not excuse harm or minimize its impact. It does, however, invite nuance — especially when evaluating behavior shaped by trauma, culture, or systemic oppression. This isn’t meant to invalidate the very real harm that narcissistic abuse can cause. If you’ve survived that kind of relationship, your experience matters deeply. My aim is simply to widen the conversation to include those who are being mislabeled — not to silence or diminish those who’ve been harmed.

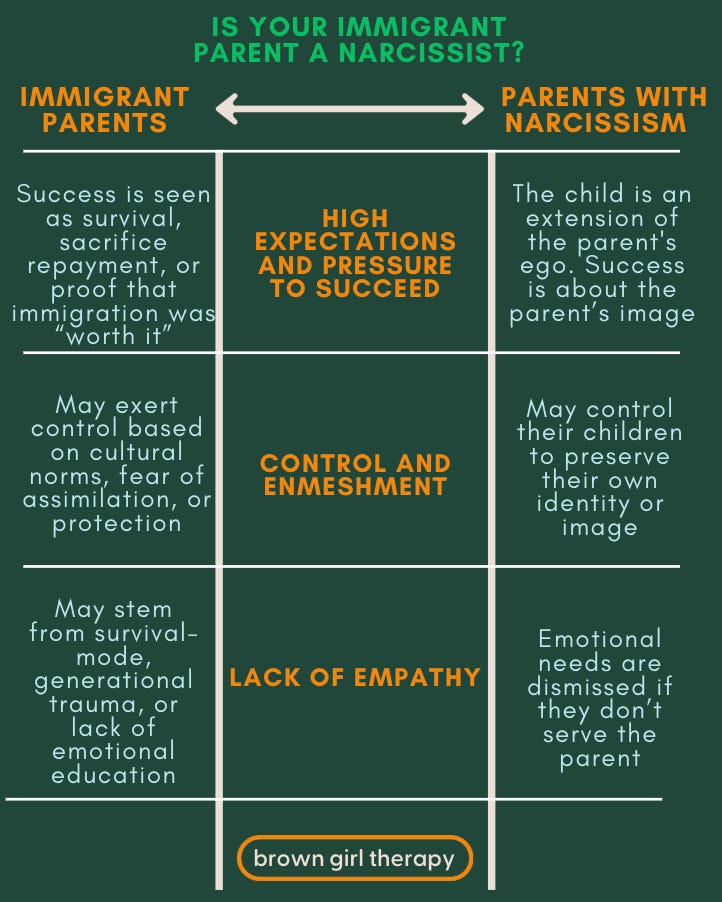

In episode 4, I pose and explore the question: Is your immigrant parent a narcissist? On social media, I even made these graphics (below).

With that said, harm is harm and if you’ve been harmed by narcissistic traits — the full episode offers you lots of tips for communicating or protecting yourself in these relationships. Again, please read the editor’s note above!

In this bonus episode I want to explore, “narcissism” — a personality trait that exist on a spectrum from mild to severe — and how trauma, survival, patriarchy, oppression and systems can actually breed these.

For many adult children of immigrants, especially from collectivist cultures behaviors that Western psychology might label as ‘narcissistic’ can actually reflect the tension between cultural survival and Western ideals.

For example, traits like assertiveness, self-promotion, or individual achievement are often encouraged — even expected — in places like the U.S. as markers of success and confidence. But in many immigrant households, these same traits might be seen as disrespectful, selfish, or shameful — because they conflict with values like humility, family harmony, and collective identity.

So when an adult child starts setting boundaries, advocating for themselves, or taking pride in their work, they might be judged by family (or even themselves) as being ‘too much’ or ‘self-centered.’ On the flip side, when they don’t promote themselves in Western spaces, like at work or in school, they may be perceived as lacking ambition or confidence.

That push-and-pull often causes deep internal conflict. And it’s crucial that we, ask: Are we pathologizing someone’s cultural dissonance as narcissism? Or are we witnessing someone trying to survive two conflicting value systems at once?”

I ask/say this because: I’ve had clients — especially adult children of immigrants — who ask me if they’re narcissists. Not because they’ve harmed others. But because they’re learning to say “no.” Because they chose rest instead of over-functioning. Because they set a boundary and felt shame instead of relief.

In systems that teach you your value comes from self-sacrifice, even the smallest acts of self-care can feel selfish. But that’s not narcissism. That’s survival. That’s unlearning. That’s healing.

And I’ve seen this pattern over and over:

You might not be narcissistic. You might be traumatized.

You might not be self-obsessed. You might be seeing yourself for the first time after years of erasure.

You might not be emotionally unavailable. You might be protecting your heart in spaces where vulnerability was punished.

You might not be manipulative. You might have learned to adapt in environments where directness was unsafe.

So many of the “narcissistic traits” people fear in themselves are actually the scars of adaptation. Hyper-independence, strategic self-promotion, emotional distance - these are often born from context, not character flaws.

This doesn’t excuse harm or minimize its impact. It does, however, invite nuance — especially when evaluating behavior shaped by trauma, culture, or systemic oppression. True narcissistic patterns can deeply affect others. And I encourage you to work with a professional if you are concerned about these traits. This isn’t meant to invalidate the very real harm that narcissistic abuse can cause. If you’ve survived that kind of relationship, your experience matters deeply. My aim is simply to widen the conversation to include those who are being mislabeled — not to silence or diminish those who’ve been harmed

And too often, marginalized people internalize that any form of self-focus is pathological. Let’s be careful with our language. Let’s make space for cultural nuance, trauma histories, and identity context. Yes, there are individuals who use pop-psychology language to avoid accountability — but this post isn’t for those people. It’s for those who are mislabeling themselves or others out of cultural confusion, shame, or survival patterns.

Why are we so obsessed with diagnosing others as narcissists? Are we avoiding relational accountability, emotional nuance, or systemic analysis? What’s the line between self-confidence and narcissism in your community? How might systemic oppression shape what looks like ‘narcissistic’ behavior? How are we rewarding this in some people and pathologizing it in others?

So: Let’s talk about narcissism — but not the way pop culture does. It’s not just selfies, arrogance, or a “toxic ex.” What if narcissism is also about power, survival, and systems of oppression? Listen to the episode for a 16-minute breakdown of this including:

scarcity mindset

Western frameworks

systems of oppression

childhood trauma

Again, to be clear, clinical narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is a serious and diagnosable condition. This discussion isn’t about that — but about how the casual misuse of the term 'narcissist' can obscure more complex realities, particularly for those navigating cultural or systemic trauma.

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Culturally Enough. to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.